[ad_1]

The new movie Oppenheimer has been bringing people to the theatres and taking them back in time looking at the creation of the atomic bomb, but a Winnipegger who was part of the project still remains in the shadows.

Louis Slotin was born on Dec. 1, 1910, and grew up in Winnipeg’s North End.

By the time he was 16, he went to the University of Manitoba, where he got both his Bachelor’s and Master’s of Science and by the time he was 25, he had a doctorate in biochemistry from London University.

“My uncle was an extremely bright person. I didn’t know him personally, he passed away before I was born. But what family tells me was that even as a young student, people recognized him as being extremely bright,” said Israel Ludwig, whose mother was Slotin’s sister.

Ludwig said after receiving his doctorate, Slotin went to the University of Chicago and started working with Enrico Fermi – an Italian physicist who created the first nuclear reactor, a project Slotin was present for.

“When Fermi got drafted into the Manhattan Project, he took my uncle with him. And my uncle was eventually promoted to the work they were doing at Los Alamos.”

At Los Alamos – the location where the secret works of the Manhattan Project took place – Slotin was tasked with developing the combat core for the ‘Gadget’ – the name of the bomb before it exploded in the Trinity nuclear test.

Louis Slotin (on the left) is seen standing next to the Gadget in 1945 at Los Alamos. (Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory.)

Louis Slotin (on the left) is seen standing next to the Gadget in 1945 at Los Alamos. (Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory.)

“My uncle was given the privilege of delivering the atomic bomb to the armed forces and they gave him a certificate calling him the chief armourer of the US armed forces.”

Ludwig also pointed out Slotin was supposed to be on the Enola Gay – the plane that dropped the bomb “Little Boy” on the city of Hiroshima, Japan – to arm the bomb and get it ready to be dropped.

“But being a Canadian, they wouldn’t let him into that part of the operation because his green card hadn’t come through yet.”

Ludwig has seen the new movie and enjoyed it, saying it was fairly accurate. While there is no direct reference to his uncle, he said there is a part of the movie that could be him.

“There was one scene where they were assembling the Gadget…and there was a person there that could have been my uncle, because that was what my uncle did at that time.”

GROWING UP IN WINNIPEG

Slotin and his family originally lived on Alfred Avenue before building a house and moving to Scotia Street at the end of Inkster.

Ludwig said Slotin didn’t live at that home for long as he was already working toward getting his Ph.D., but had the reputation in the community of being extremely smart.

“I remember being told by a man…who had a grocery store that my uncle and his friends would hang out and he said they would get to talking about the mathematics and physics formulas that they were learning at school and they would start writing them out on these big rolls of butcher paper in that store.”

He said Slotin and his friends would end up writing so many formulas that the store would run out of butcher paper.

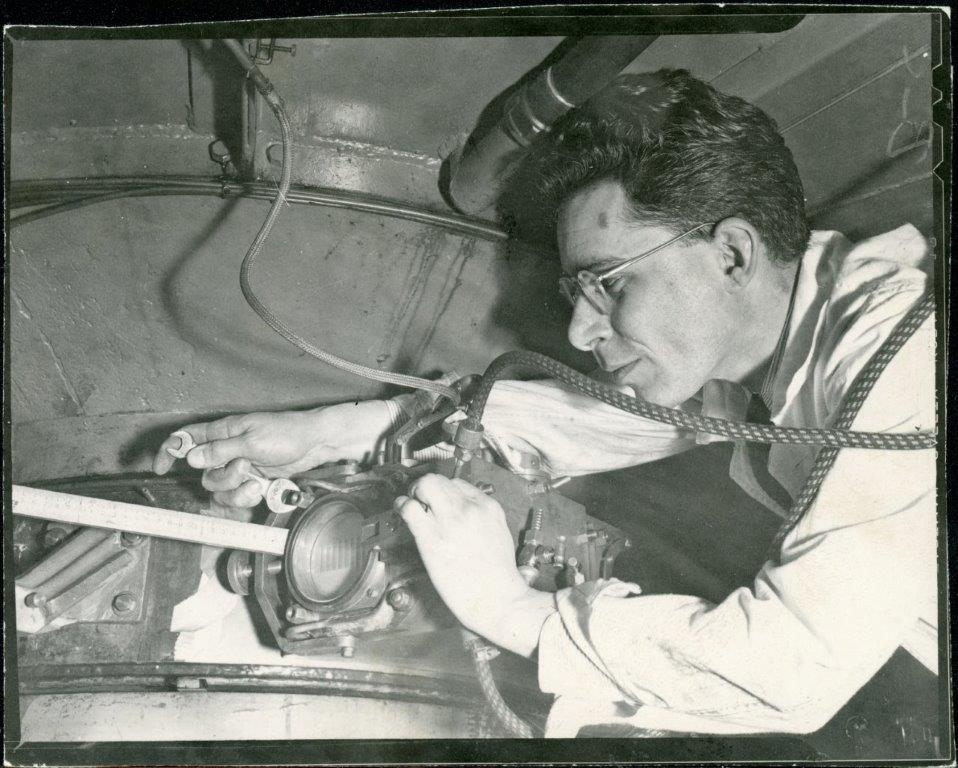

Louis Slotin working in an undated photo. (Source: Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada)

Louis Slotin working in an undated photo. (Source: Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada)

Ludwig also heard stories from his aunt who would play cards with Slotin and his friends. Ludwig said his aunt would always get annoyed because Slotin would deal the cards and then before any moves could be made, he would already know how everyone would play, seeing the outcomes before they would happen.

Now, not far from the Slotin home on Scotia, there is a plaque that honours Slotin and his scientific contributions.

“If you go into the North End to Luxton Avenue, you go down to the end of the east end of Luxton Avenue, it ends up at the Red River Bank and right there on that bank is a little park…and there’s also a plaque and the plaque is named after my uncle.”

‘TICKLING THE DRAGON’S TAIL’

Following the war and the use of the two atomic bombs in Japan, Slotin stayed at Los Alamos until 1946.

According to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Slotin had planned on returning to teaching but first had to train his replacement.

One of his jobs was performing criticality tests – bringing the core of the bomb to the point before a fission reaction – which was known as “tickling the dragon’s tail.”

The test involved having two half-sphere shells of beryllium and a small plutonium core and the closer the two halves got, the stronger the fission reaction was.

To do this test, Slotin would use a screwdriver to separate the two halves. However, on May 21, 1946, Slotin’s hand slipped and it caused the core to go critical.

Slotin Building in Los Alamos. This is where Louis Slotin died following a critical reaction of one of the atomic cores. (Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Slotin Building in Los Alamos. This is where Louis Slotin died following a critical reaction of one of the atomic cores. (Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory)

According to the laboratory, heat and blue light filled the room.

“My uncle jumped on it immediately and pulled the hemispheres apart, stopped the chain reaction and saved the lives of everybody in the lab,” said Ludwig.

While putting himself on the core, Slotin was exposed to a more than lethal dose of radiation and died in hospital nine days later of radiation poisoning. He was 35 years old.

“My family were always very proud of him,” said Ludwig. “This was a brilliant man the world lost and he clearly was a very moral man who, that without a second thought, sacrificed his life in order to save others in the lab.

“The biggest loss, that I’m told, is he was getting interested in using radiation to combat diseases, particularly cancer, and that’s why he wanted to go back to the University of Chicago to continue that kind of research.”

– With files from CTV’s Kimberly Rio Wertman

[ad_2]

Source link