[ad_1]

On 24February 2022, two men – a Turk called Namik Kemal Asutay and a Serbian by the name of Emrula Delibalta – drove to Belgrade’s Nikola Tesla airport to pick up two young Turks who had just landed.

The two arrivals had no trouble entering Serbia, in part thanks to the visa-free regime the country shares with Turkey but also because of fake guarantee letters Delibalta had written two days earlier vouching for the men and their reasons for visiting.

In an Opel Insignia with French licence plates, the party of four left the airport and headed for the ‘Koker’ hostel in Pozarevać, a town some 80 kilometres southeast of Belgrade.

At around 3pm a man called Erkan Sorovać collected the two Turks and drove them to Backa Topola, a town roughly 30 kilometres short of the border with Hungary. After changing both car and driver, the group approached the Horgos border crossing at 6.50 p.m., when it was already dark. Ten minutes later, in the company of unidentified guides, the two Turks set off across the Serbian part of the border, walking slowly at the edge of the crossing hidden behind a convoy of trucks queuing to pass customs.

Receive the best of European journalism straight to your inbox every Thursday

Sorovać also crossed the Serbian side of the crossing, legally, and stopped by toilets in no-man’s land where he met the two Turks and gave them instructions to cross the Hungarian side too. It worked, and a few moments later, now on Hungarian territory, a car picked up the pair and they drove off.

This simple operation was repeated a number of times between February and November 2022, when, in the city of Mardin in southeastern Turkey, Serbian police arrested Sorovać as the suspected ringleader and two other men, accusing them of illegally smuggling Turkish citizens into the EU at a price of €2,400 per person.

All-inclusive package

According to a copy of the court verdict of 9 December 2022 and obtained by BIRN via a Freedom of Information request, the group offered an all-inclusive package: airport pick-up, fake guarantee letters, accommodation, transport to the border with Hungary and pick-up on the other side.

According to the findings of a BIRN investigation, young Turks fleeing economic hardship and political polarisation under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan are increasingly using Serbia as a transit point to enter the EU illegally; the smuggling industry is flourishing.

Last year alone, a total of 860,719 Turkish citizens entered Serbia, some 62,000 more than in 2019, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Economic hardship driving migration from Turkey

A number of European countries have reported an increase in Turkish asylum seekers; last year in Germany, there were nearly 24,000, representing a 200 per cent increase on the year before and putting Turkey in third place behind Syria and Afghanistan in terms of the origin of asylum seekers.

As a whole, in the 27 states of the EU plus Norway and Switzerland, 55,000 Turkish citizens applied for asylum in 2022, more than double the number in 2021.

Most are fleeing primarily for economic reasons, said Ahmet Erdi Öztürk, a professor of politics at London Metropolitan University. “First is economics,” he said. “Former middle-class people are looking for new economic opportunities in Europe. Secondly, young people do not see a future in Turkey ruled by the autocratic policies of Erdoğan. They see Europe as a salvation politically, socially and economically.”

As long as the EU continues to resist giving more visas to Turkish citizens, Serbia will likely remain a hub for illegal crossings, Öztürk said.

“EU countries do not give visas easily,” he told BIRN. “The EU thinks that if it gives tourist visas easily they will not come back to Turkey. Therefore, people use illegal ways to reach the EU.”

According to Turkish foreign ministry data, before the COVID-19 pandemic, on average roughly a million Turkish citizens a year applied for visas to travel abroad. In 2022, the number shot up to 3.5 million. The EU refused nearly 20 percent of Schengen visa applications.

Concerned that migrants were exploiting more relaxed visa conditions in the Balkans, the EU urged several Balkan countries last year to revisit visa policies towards a number of countries, including Turkey.

Istanbul: Unofficial people smuggling capital

Smugglers, migrants, police informants and intelligence officials have all told BIRN that Istanbul has emerged as a people smuggling hub, where many of the ringleaders are based, including those running operations in Serbia.

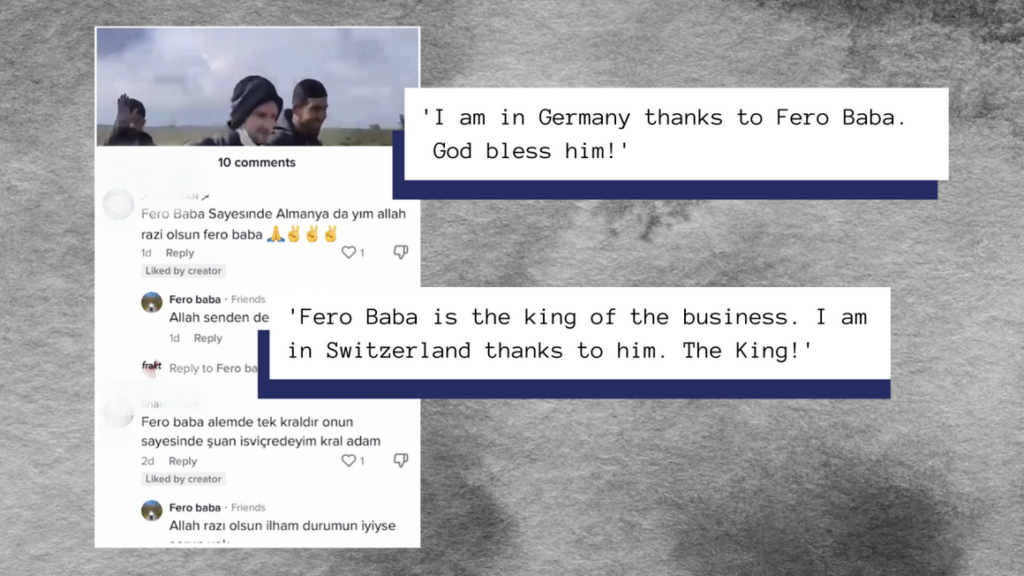

The process usually begins online, on platforms such as Facebook, TikTok or WhatsApp, where would-be migrants seek out smugglers.

On TikTok, for example, using the hashtag Umudayolculuk, or “Journey to Hope”, there are any number of videos advertising the work of smugglers and which have registered thousands of views. The comments are full of people asking for details, including prices.

Facebook also features many groups for people wishing to take the Balkan route, including one called “Europe’s Asylum Ways” where questions are asked about prices, routes and possible obstacles, such as the police and the Serbian terrain.

Prices vary from smuggler to smuggler, depending on the starting point and the level of organisation. One Syrian smuggler told BIRN that the price goes as high as €5,000, starting in Istanbul. From Serbia, however, the price drops to between €2,500 to €3,000. Experiences vary given the nature of the market.

“Someone said€ 3,500, someone else agreed for €4,000,” Sadik, from Diyarbakir in southeastern Turkey, told BIRN in Belgrade. “Someone said if I come to Serbia, they would get me across the border for €2,000.”

Key to the entire transaction is the question of trust, and that’s where the so-called “banks” or “offices” come in – places where migrants leave money with middlemen operating under a traditional “hawala” system of money transfer.

Hawala is Hindi for “trust”. One of the oldest and most cost-effective ways of transferring money, today it is used extensively by criminal groups, among them people smugglers.

In hawala “safe houses” – often cafes, branch offices of airline companies, currency exchange offices, or jewellery stores – migrants and refugees leave money for a smuggler, who can only collect when the “client” safely reaches his or her destination. The “third party”, the middleman, receives a commission. If the agreement is broken or the client does not reach Europe, the money is safely returned.

Sources in the smuggling community have told BIRN that for Turkish citizens planning to enter the EU via Serbia, the hawala services are often located in the Aksaray neighbourhood of Istanbul’s old town, a trade, foreign exchange and commodity centre for centuries.

Some “hawaladars” have good reviews, such as a person called “Senay”.

“Everyone works with Senay; she’s like a bank,” reads one comment in a Facebook group. Another describes Senay as one of the two trusted hawaladars in Istanbul.

A person asked whether Senay or Hamza are safe as hawaladars. “They are trustworthy,” the account that went by the name Ali Ihsan wrote in a Telegram group viewed by BIRN. “We will help with anything.”

Even if a migrant opts to go without the help of smugglers, they frequently seek out companions to go with them. Again, on social media:

“I will go to Serbia in two days and then I will try to pass the border by myself,” one person wrote on Facebook. “I need one trusted person to accompany me.”

Others, however, say travelling without the guidance of smugglers carries its own risks. “Serbian police, Afghans, Kurds, Turks, and people from every nation earn money corruptly…[It is] a place where human life is very cheap,” one member of a Facebook group wrote to another.” A lot of people have been murdered in the forests just because they crossed into a gang-held area.

For those who are undeterred by such warnings, the Nikola Tesla airport on the outskirts of Belgrade is usually the first stop.

Fake Turkish papers

The BIRN investigation found that some refugees and migrants – who are not Turkish citizens – are using Turkish papers and passports, sometimes faked, to enter Serbia.

Before attempting to cross the border into the EU, some of these refugees and migrants get rid of the documents or hand them to smugglers who can then give them to new “clients” in Turkey.

“When they go to cross the border they drop their Turkish documents, and sometimes they even erase their faces from the document,” said a source who collected such documents on behalf of smugglers.

“They [the smugglers] give them [the documents] to other groups. And everything starts again, just with other people.” Many of those who use such methods are of Syrian origin, the source said.

Human rights lawyer Nikola Kovačević, who has worked extensively with asylum seekers, confirmed the practice.

“In my experience, it can be said that a certain number of refugees use fake Turkish documents – passports and, as of recently, ordinary identity cards – in order to enter Serbia,” Kovacevic told BIRN. “Of course, it’s hard to say how widespread this phenomenon is, but it happens.”

Sadik, who decided against hiring a smuggler in Istanbul, said that on arriving in the Serbian capital he headed straight for a café and restaurant called Mesopotamia, near the central bus station. Mesopotamia is a hawala location, BIRN revealed in an investigation published in 2021.

“This is like a gathering point,” he said of the area around Mesopotamia. “There is big business there. The smugglers bring a bus to take the people to the border.”

The more organised smugglers, however, are picking Turkish citizens up directly from the airport, by private car or taxi.

But even if a Turkish migrant has not hired a smuggler in Istanbul or Belgrade, they will still need to pay the Afghan, Moroccan or Syrian smuggling gangs that control the border areas with Hungary to let them cross. “If they have a smuggler then he still needs to pay a “cut” for each person, a few hundred euros for each,” a Syrian smuggler told BIRN. “If they go alone then they pay directly to the border smuggling gangs and then the price can go much higher.”

Turks have little choice. “They can’t negotiate the woods, they don’t know the route and the smugglers are ripping them off,” said the Sombor taxi driver, who said he often drives Turkish migrants to border crossings controlled by Afghans near Subotica.

Worth the risk

Samil, who left Turkey in 2021, said his compatriots were willing to take the risk for what they believe will be better lives in the West.

“People in Turkey live like slaves,” said 30-year-old Samil, who left Turkey after an investment in the hospitality industry failed and now works in Paris as a small-time smuggler of migrants through Bosnia and Herzegovina, the route he himself took. “They work 14-15 hours a day. They don’t have any social activities. Work, home, work, home. This is slavery anyway.”

Many of the Turkish arrivals in Serbia seek out construction work in order to make enough money to cross illegally into the EU.

Even if they make it, Turks deemed economic migrants can face a long period of illegality; those classified as “political fugitives”, however, have better chances of receiving asylum, spurring what may be another tactic to play the system.

“I can make it happen; I can make them initiate a court case,” Omer, one of the Turkish migrant BIRN accompanied during this investigation, said in a conversation with a Turkish couple also seeking to enter the EU.

The woman in the couple concurred: “I heard there’s a guy doing this for 3,000 Lira [roughly €150],” she said.

Journalists Zeynep Şentek and Orhan Şener also contributed to this report.

👉 Original article on Balkan Insight

[ad_2]

Source link