[ad_1]

This article is reserved for our members

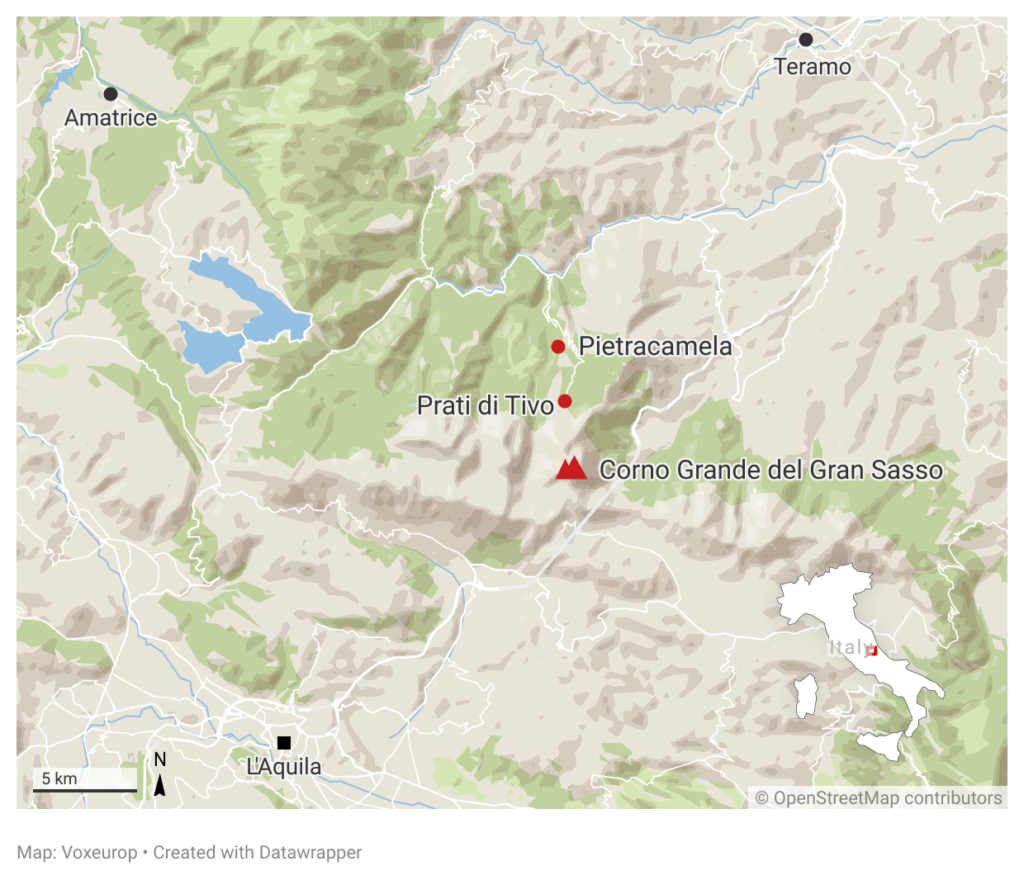

Pietracamela. At the end of the winter season, Pietracamela, in central-southern Italy, looks like a ghost village. A lone dog barks, curtains twitch behind wood-framed windows. Between the two highest peaks of the Apennines, the glacier creaks as its ice melts. In spring, avalanches are frequent. A thousand metres downstream, small rivers swell. Pietracarmela’s residents are confronting the effects of climate change.

Europe’s mountains are warming at almost twice the rate of the rest of the continent. This gives us a glimpse of the future: increasingly extreme weather events, and increasingly extreme consequences. In the mountains, snowfalls are either rarer or more intense, weather conditions change unexpectedly, and glaciers inevitably retreat. Local communities are retreating with them.

Receive the best of European journalism straight to your inbox every Thursday

Gran Sasso, Italy’s highest mountain, offers an illustration of this. Pietracamela, the nearest village to Gran Sasso, was once a fashionable tourist destination with three clubs and a piano bar. That is now a memory. The petrol station still displays prices in lira, while the four luxury hotels are now closed during the winter.

Calderone, Gran Sasso’s glacier – one of the southernmost in Europe – is losing its status. Or rather, it has already lost it.

Between 1999 and 2000 it split into two smaller pieces, two “glacierets” or “snowfields” in scientific terminology. This process, which downgraded Calderone to a “glacial system”, coincided with the shortening of the ski season.

Older residents remember that it was possible to ski on the slopes of Prati di Tivo from November to May, and even longer on the glacier. Now the first snow often falls after New Year’s Day. “In the last five to ten years, snowfall has been rare in winter, but very frequent in April and May,” confirms Massimo Pecci, an expert on the Calderone at the Italian Glaciological Committee. Pecci, who is also a professor of glaciology and an avalanche specialist, explains that the situation is similar in many of Italy’s nearly four thousand mountain communities.

Ski lifts currently do not work and artificial snow systems remain idle even when potentially useful in early winter. In winter and spring, the only tourists who come are those interested in ski mountaineering. This sport requires strenuous ascents and makes less use of local businesses.

Dangerous snow

First possible conclusion: changing precipitation is the main factor affecting winter tourism. In a way, this interpretation is correct: Pasquale Iannetti, my guide on the glacier, says that the walk from Prati di Tivo to Calderone usually takes three hours, but on 1 May it took almost ten because “the snow conditions during the ascent were unprecedented, the snow was extremely muddy”. In other words, dangerous.

However, to emphasise the difficulties of winter tourism is to oversimplify. The reality is more like a complex vicious circle: winter activities are more difficult and costly to plan for; so mountain villages have less stable income; so they attract fewer residents; and so support for new public investment, including infrastructure, declines.

This, in turn, will slow down any revitalization. For example, the owners of old stone houses, which are less resistant to earthquakes, fear to return. They are thinking of the earthquakes that have struck the area twice in seven years in the last 15 years. Others cannot stay overnight in their houses because they are still being renovated.

Seismic zones

The area between Abruzzo and Lazio was badly damaged by the 2009 and 2016-17 quakes. Reconstruction is taking longer than in more populated or better known towns, such as the epicentres of L’Aquila and Amatrice, where the death toll was higher.

The delays in Pietracamela are partly due to its geographical location and the lack of local shops. Poor infrastructure, including roads, is an obstacle. Construction workers have to travel by van every morning, often in extreme weather conditions. The nearest supermarket is about 20 minutes away by car.

Some of the existing infrastructure and buildings may fall into disrepair, and with them the village may lose its identity. “Houses that were used as holiday homes are still closed. The owners have lost the habit of coming back,” comments Salvatore Florimbi, Pietracamela’s municipal councillor.

Given these developments, it is not surprising that the state-owned operator of the local ski facilities has gone bankrupt. For more than four years, people have been trying to find a solution to what residents call a case of mismanagement of public infrastructure. The functioning of the cable cars is crucial to the recovery of tourism in the area, many locals say.

As the pie shrinks and business activity declines, divisions are emerging among those locals. Indeed, tensions are hampering cooperation, to the point that after the 2020 local elections the new administration spoke of ‘liberation’. This word has a charged meaning in Italian, referring to the fall of the fascist regime.

It could be argued that this is just a matter of tourism and socio-economic difficulties. But that is not quite the case. The financial flow associated with tourism is essential for basic services. This includes snow removal, and in particular controlled avalanches, which are artificially triggered to prevent the accumulation of sn…

[ad_2]

Source link

![[Column] In 2024, Europe’s voters need to pick a better crop of MEPs [Column] In 2024, Europe’s voters need to pick a better crop of MEPs](https://media.euobserver.com/c03ef5b972e44db01aa947f52f631866-800x.jpg)