[ad_1]

When the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in March about restricting access to the abortion drug mifepristone, Elisa Wells, co-founder and co-director of Plan C, was ready.

Plan C, an information resource that connects women to abortion pill providers, almost immediately saw a spike in searches for the medication.

With Florida’s Supreme Court paving the way for the state’s six-week abortion ban, Wells says she’s expecting even more search activity and more creative thinking from providers.

“When these egregious decisions happen, first, they cause harm,” she says. “And the second thing that happens is people get organized and mad and take action.”

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in its 2022 Dobbs decision, upending abortion access in the U.S., a network of abortion providers has sprung into action, weaving an abortion safety net across the country even as the procedure has been effectively banned in 15 states.

Providers such as Aid Access, Hey Jane and Just the Pill operate both within and outside the established health care system — including mailing abortion medications to women in states with bans, setting up mobile clinics and offering financial assistance — often staying in close contact with one another.

Many of those efforts center on access to abortion medication by mail, which the Food and Drug Administration made fully legal in 2021, creating a sort of “sisterhood of the traveling pill” that keeps groups connected as new restrictions on abortion arise.

Wells says Plan C called different providers for a meeting on how best to pivot in the changing abortion landscape.

“We had meetings where we introduced the providers to one another,” she said. “All of these groups that normally would be competing with one another to come together and discuss, you know, how can we make a difference? How can we collectively address this issue?”

One such group is Aid Access, an online-only service based in the Netherlands. Originally a resource for women in the U.S. to get abortion pills from overseas, providers for the organization now ship pills from within the U.S. under telemedicine shield laws. The shield laws have been enacted in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont and Washington. The laws protect providers who prescribe and ship abortion pills to patients who live in states where abortion is banned or severely restricted.

“Before we had the shield law, we were mailing pills to the blue states, and only [pills from] overseas could be sent to the restricted states,” said Dr. Linda Prine, a New York City-based shield law provider.

After New York’s shield law passed, Prine said, “the first month we sent about 4,000 pills into restricted states, and now we’re up to around 10,000 pills a month.”

In a basement in upstate New York, another Aid Access provider who asked to not be identified for safety reasons underscored the importance of sending these pills from the U.S., rather than overseas.

“Sometimes they got stuck in customs,” the provider explained as more than 100 prescriptions were being packaged around them, preparing to be shipped into states with bans.

“When you’re doing a medication abortion, the faster you can get these medications, the better,” the provider said in an interview. “It’s easier, there’s less bleeding, there’s less cramping, and not to mention the anxiety that these women go through when they’re waiting for those medications to get to them in the mail.”

Aid Access providers say they’re sending pills to some who are in the most desperate situations — people who are willing to risk going outside the established health care system to access abortion services. The organization is exploring contingency plans in the event that access to the abortion pill through the mail is disrupted.

“We have so many patients who write to us who’ve been raped, who can’t travel,” the provider explained. “So we have to come up with other ways. I would say the last resort would be that these medications come again from overseas.”

And while shield laws have yet to be challenged in courts, anti-abortion groups have taken notice.

“The fact remains that just because you are sitting in California does not mean that you are not violating the laws of Florida, Texas and 30 other states,” Katie Daniel, state policy director for the anti-abortion group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, told NBC News. “So I think they have a false sense of security about this.”

In the six months after Dobbs, researchers saw an increase in women getting abortion medication outside the traditional health care system, with more than 27,000 additional instances, according to a recent study in the journal JAMA.

“These are groups like Las Libres, WeSaveUs, Arkansas Together,” said Wells, who was a co-author of the study. “They’re serving a significant number of people for an all volunteer-led effort.”

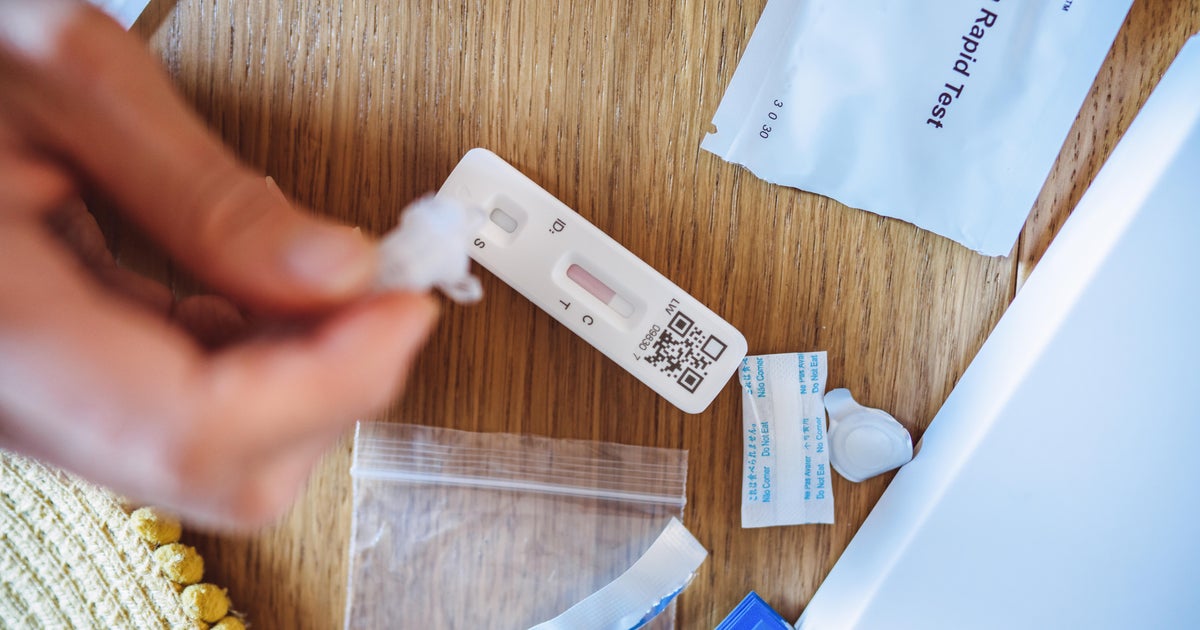

Even within the traditional health care system, abortions via medication are increasing, too. Medication abortions accounted for 63% of all abortions in 2023, up 10% from the year before, according to research from reproductive rights think tank the Guttmacher Institute, making it the most common method for terminating a pregnancy.

New York-based Hey Jane has seen that demand firsthand. Founder Kiki Freedman, an early Uber employee, launched the telemedicine-only abortion provider in 2018 after seeing other startups deliver medications and savings to customers via online-only prescription services. After the FDA eased restrictions on mifepristone prescriptions during pandemic, allowing women to get the abortion pill through the mail, Hey Jane took off. The company has shipped abortion pills to at least 50,000 patients, according to a statement.

“We have the added benefit of this sort of geographic fluidity where a doctor in New York can serve a patient in Illinois, or New Mexico if the doctor in New Mexico or the provider in New Mexico is busy,” said Freedman. “The other piece is financial accessibility and being able to access scalable ways of doing that, so via insurance, in particular.”

Hey Jane only prescribes and ships abortion medication to states where it’s legal, marking a difference from shield law providers and organizations like Aid Access.

Access to medication abortion helps patients avoid traveling and wait times at in-person clinics, and allows them to take the pills in private at home. While providers who ship to states with bans have struggled with traditional payment platforms, Hey Jane’s focus is on keeping access covered by insurance.

“Still, 75% of abortions are taking place in these 20 states we’re in. It’s still where the vast majority of care occurs,” said Freedman. “It’s not like access in those states has been seamless to date, right? It’s always been difficult even there, and particularly post-Dobbs, wait times and things like that have really surged within those states.”

Just the Pill provides abortion access to women in states with bans using discreet mobile clinics set up just across state lines.

The group has bulletproof vans in Colorado, Minnesota and Montana, and a brick-and-mortar location in Wyoming. Appointments are conducted via telemedicine, always within a state where abortion is legal, making shield laws unnecessary, a backstop a Just the Pill provider said is intentional, so care won’t be interrupted if the shield laws are challenged.

“I totally support what these other organizations are doing,” she said in an interview, asking not to be identified for safety reasons. “I’m cheering them on from afar, but want to make sure our service isn’t challenged.”

Just the Pill works with abortion funds, which provide financial assistance to patients who are seeking the procedure, to help patients travel across state lines for their appointments. After a telemedicine visit, pills are then prescribed and patients can pick them up and take them, all within the borders of a state where the procedure is legal. Because Just the Pill’s clinics are mobile, they can travel along the borders of banned states and ensure they get as close as possible to women traveling from rural areas or long distances for care.

Meanwhile, Plan C is already working with more international pill providers to help with telehealth prescription access in the U.S. if telehealth visits for mifepristone are affected here, Wells said.

“We know we live in a time when anything can happen,” Wells said. “We want to have as many alternate routes and access as possible. Many eggs and many baskets.”

[ad_2]

Source link