[ad_1]

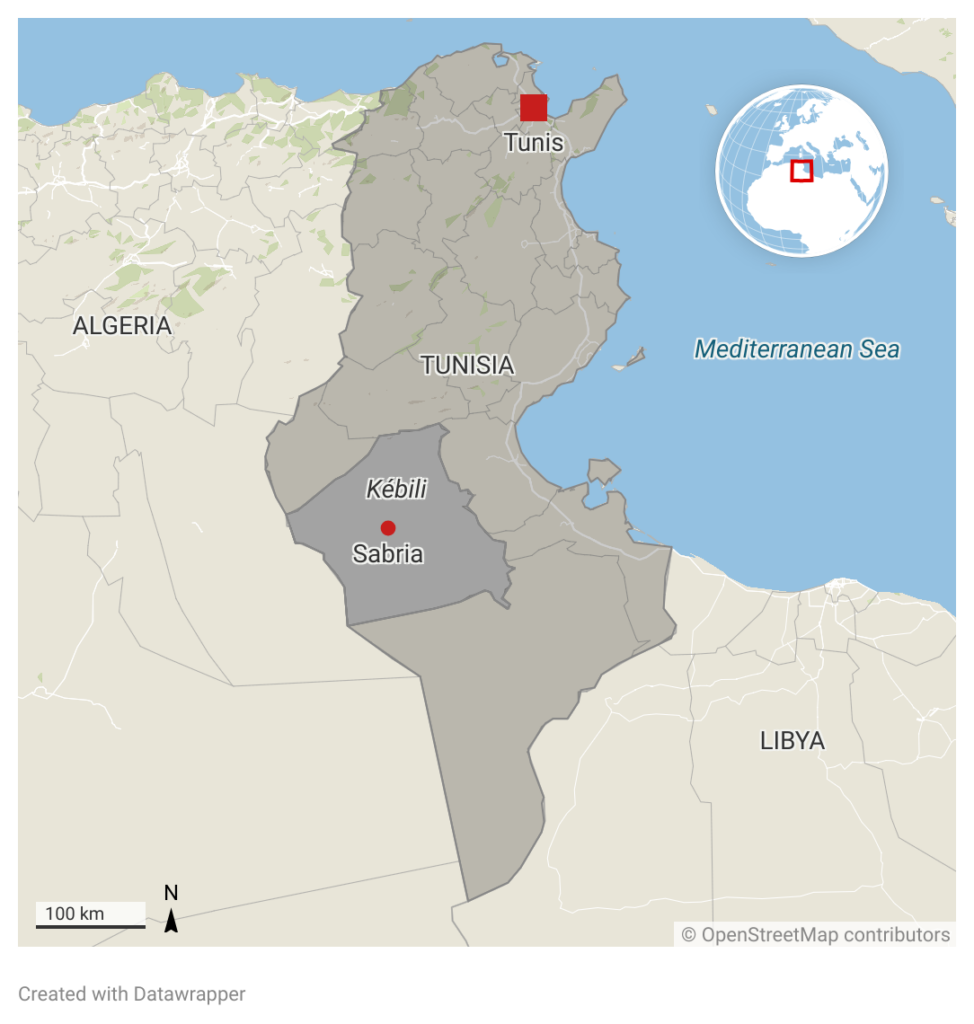

It’s hard to imagine that the landscape of Kébili, near Douz, at the gates of the Tunisian Sahara, is dotted with gas and oil wells. A protected wetland, the area is popular for its eerie landscape of pale salty water puddles set in the middle of the desert.

But it was here, in the Kébili region, that the sites of the Jersey-based French oil companies Perenco and Serinus were confronted in 2017 with repeated strikes and sit-ins organised by local civil society, which has been calling for better social and environmental monitoring of the two foreign companies operating in Tunisia since 2012.

The protest led to the signing of a 114-point agreement with civil society groups. But the extraction sites were classified as “military zones”, which prevented any attempt at protest – or indeed at monitoring the activities of oil and gas companies.

After Perenco, which was taken to court in France in November 2022 by the associations Sherpa and Friends of the Earth for the pollution caused by its activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it is now the turn of the company Serinus.

Registered in Jersey (an island between the UK and France, considered by some countries to be a tax haven), the company controls Winstar, the Tunisian operator responsible for exploiting the Sabria oil field in Kébili, whose extraction practices are equally dubious.

A “small company” owned by a Polish energy giant

The fracking technique involves injecting water, mixed with hundreds of toxic additives, at very high pressure. This chemical solution can cause serious pollution of any groundwater layers that may be intersected by the drilling process.

Suc…

[ad_2]

Source link